The Investing Mistake That Can Cost Your Entire Wealth

Why growth is not a proxy for value creation - and how not to lose money by believing it is

Sponsored Content - Presented by Rebound Capital

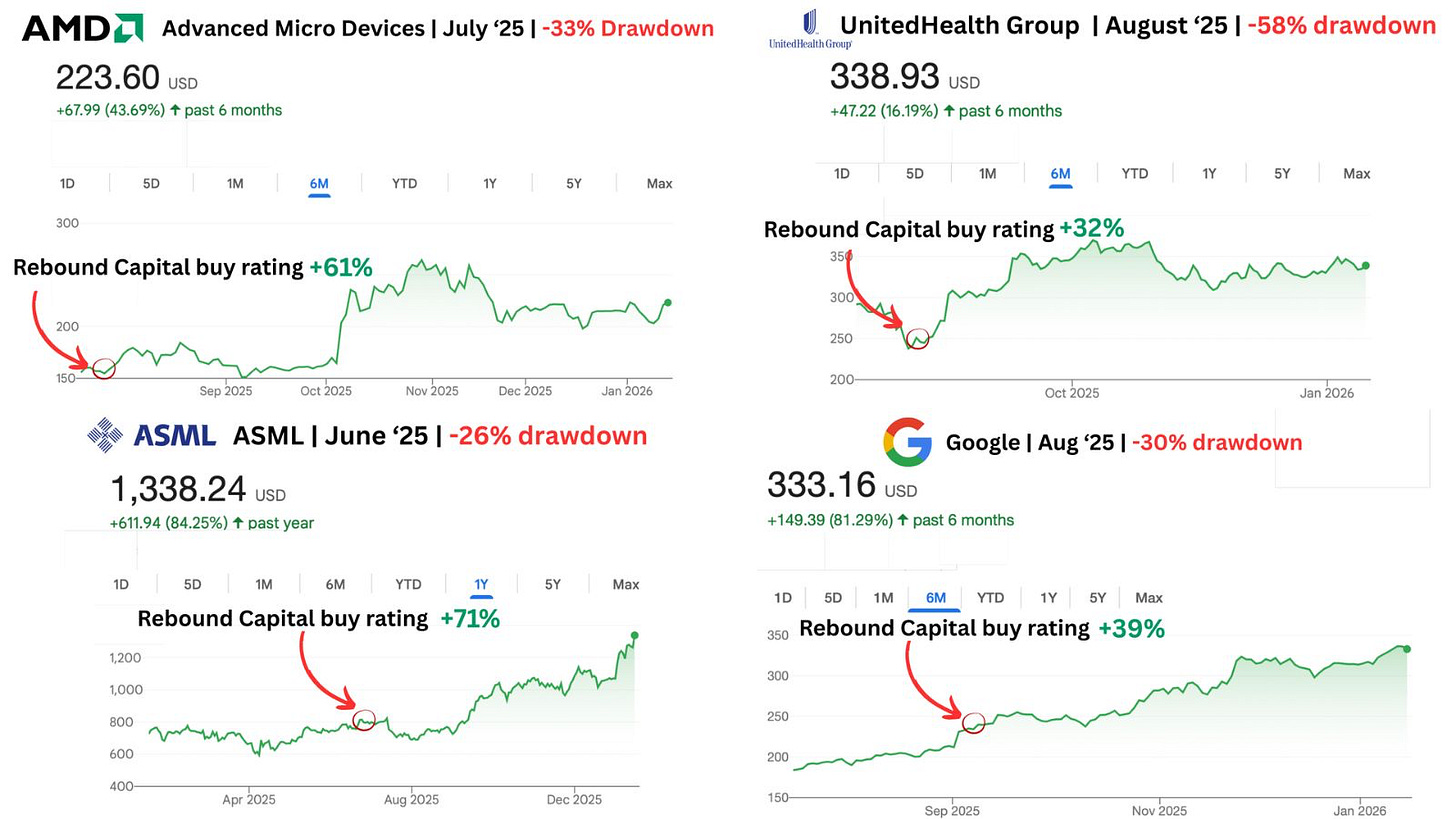

Top 10 Rebound Stocks for 2026

Meta once dropped 70%. Netflix: 50%. Amazon: 40%. Every investor had ruled them out, citing “the companies were done”.

But they all rebounded - Meta: 690%. Netflix: 540%. Amazon: 153%.

Every world-class company suffers deep drawdowns. Rebound Capital identifies high-quality companies undergoing drawdowns to capitalize on their eventual rebound.

Just last year, they identified ASML (up 58%), Google (up 40%), and AMD (up 61%) as ideal rebound prospects. Jimmy Investor readers can now unlock their exclusive 25-page report on the top 10 rebound opportunities for 2026 for free!

Thanks to Rebound Capital for sponsoring this issue.

If you would like to feature your brand on Jimmy’s Journal, please contact us at jimmysjournal@substack.com.

Hi, Investor! 👋🏼

I’m Jimmy, and welcome back to another edition of Jimmy’s Journal.

For the second time in little more than a decade, markets are falling back into a very old and very expensive habit.

They are paying for growth as if growth, by itself, were proof of value creation.

It isn’t.

It never was.

And confusing the two is one of the most reliable ways investors manage to permanently impair capital - even while holding companies that look, on the surface, exceptional.

Growth is easy to celebrate.

Value creation is much harder to measure.

That gap between what is visible and what actually matters is exactly where this mistake is born.

The Mistake:

At a very basic level, value creation has nothing to do with how fast a company grows.

It has everything to do with how efficiently it uses capital.

A business creates value only when it can invest capital at returns above its cost of capital.

Growth is only a mechanism.

Returns are the outcome.

A company can double its revenues, enter new markets, launch new products and expand its footprint globally - and still destroy value if the returns on those investments are poor.

Yet, in practice, investors continue to treat growth as a shortcut for economic success.

High growth is interpreted as strategic superiority.

Low growth is interpreted as stagnation.

This mental shortcut is convenient, and it’s also wrong.

Found this content valuable? Share it with your network! Help others discover these insights by sharing the newsletter. Your support makes all the difference!

Why is This Mistake so Common?

Because growth is visible.

It fits perfectly into headlines.

It fits into quarterly earnings slides.

It fits into short-form posts and social media narratives.

Revenue growth, user growth and market share gains are easy to communicate, easy to compare and easy to celebrate.

Value creation is not.

Understanding returns on capital requires:

reading financial statements beyond the income statement,

understanding how much capital is actually tied to operations,

separating operating performance from financing decisions,

and paying attention to how assets and working capital evolve over time.

This is slow and uncomfortable work.

Not coincidentally, this is exactly what we spend a lot of time on here at Jimmy’s Journal.

Markets naturally gravitate toward what is simple and visible - not toward what is economically correct.

Enjoying the content? Don’t miss out on more exclusive insights and analyses. Subscribe now and stay updated.

ROIC: The Real Value Creation

ROIC is the cleanest way to observe whether a company is actually turning growth into economic value - not just into a bigger business.

More than just a ratio, as Michael Mauboussin himself points out, ROIC should be treated as the outcome of a company’s competitive strategy.

In other words, understanding how a company earns its ROIC is far more important than the level of the metric itself.

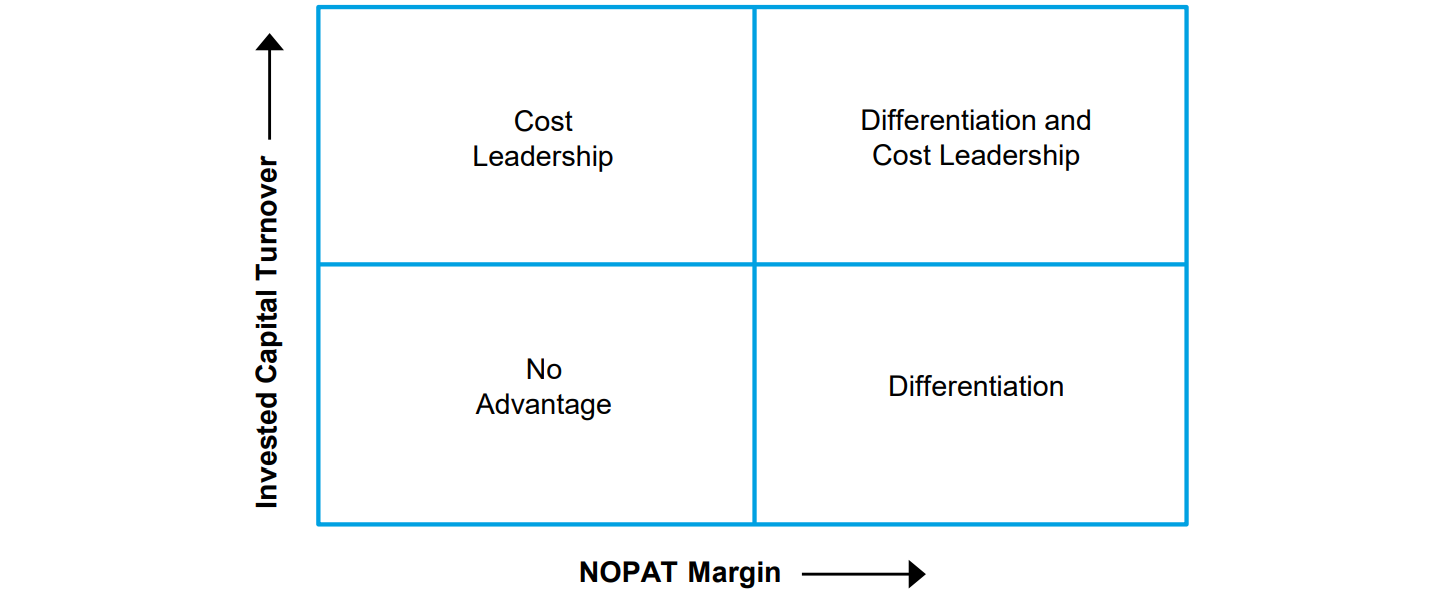

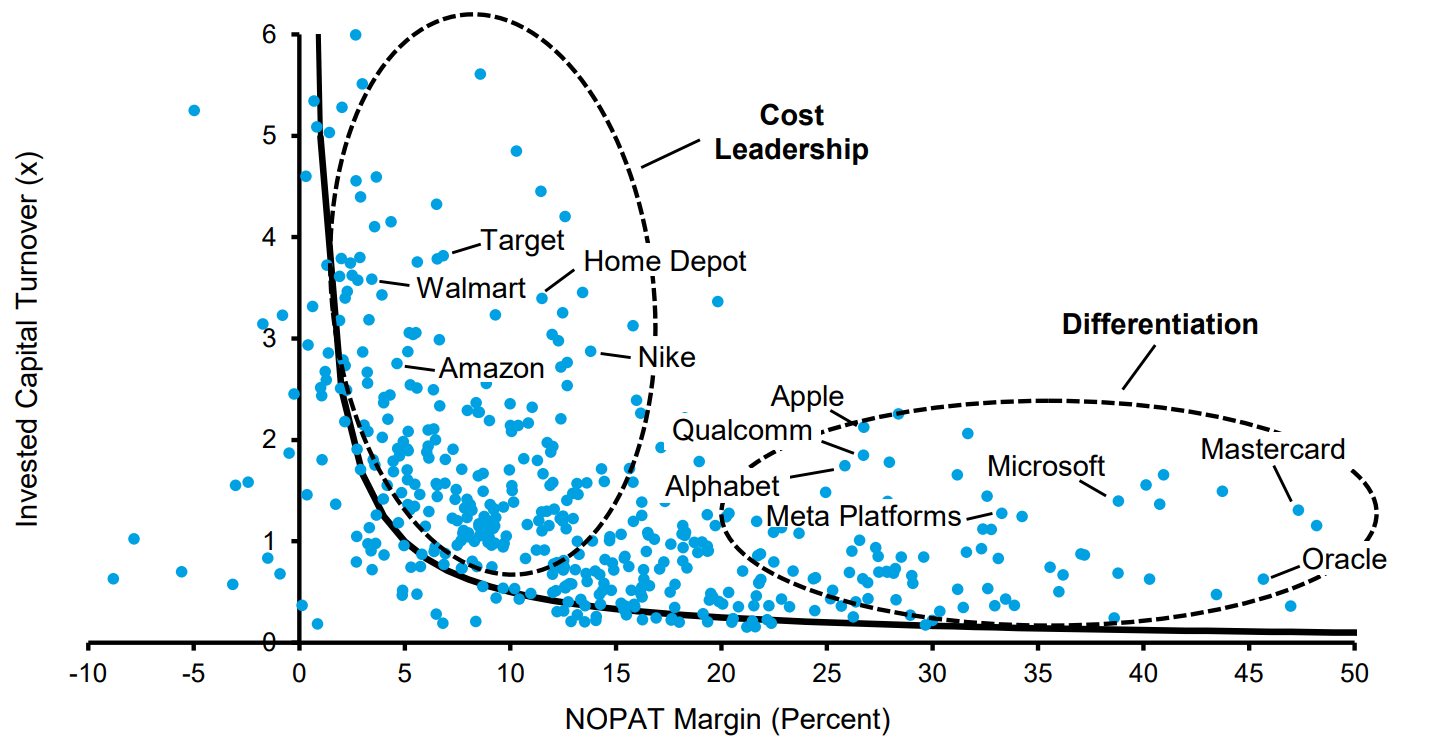

At its simplest, ROIC can be broken into two drivers:

ROIC = (NOPAT ÷ Sales) × (Sales ÷ Invested Capital)

The first tells you how much profit the company extracts from each dollar of revenue - its operating margin.

The second shows how efficiently it turns invested capital into sales - its capital turnover.

This lens matters because two companies can post the same ROIC while relying on completely different economic engines.

Some businesses earn high returns through differentiation and pricing power, with strong margins but slower capital rotation.

Others achieve similar returns through scale, operational efficiency and cost leadership, with thin margins but very fast capital turnover.

The number may look identical on the surface.

The strategy behind it is not.

And once you understand whether returns are driven by margins or by capital efficiency, you are in a far better position to judge whether growth is actually compounding value - or merely expanding the footprint of a mediocre business.

ROIC, in the end, is not just an accounting outcome.

It is the economic fingerprint of a company’s competitive positioning.

Found this content valuable? Share it with your network! Help others discover these insights by sharing the newsletter. Your support makes all the difference!

The Math is Unforgiving:

Growth is not free.

Every additional dollar of revenue requires capital - whether in the form of operating assets, working capital, infrastructure or acquisitions.

The key relationship is very simple:

Growth = Reinvestment Rate x ROIC

Or, rearranged:

Reinvestment Rate = Growth ÷ ROIC

This identity alone already explains why growth can mean radically different things for different businesses:

Company A: 30% ROIC and a target operating profit growth of 10% per year.

To sustain this growth, following the relationship above, the company needs to reinvest only 33% of its operating profit (10 ÷ 30).

In other words, only one-third of the cash generated by the business must be reinvested. The remaining two-thirds can be returned to shareholders or allocated opportunistically.

This is what capital-efficient growth looks like.

Company B: 5% ROIC and a target operating profit growth of 10% per year.

To sustain the same growth, following the same relationship, the company must reinvest 200% of its operating profit (10 ÷ 5).

In practice, this means the business cannot fund its growth internally. It must rely on new equity, higher leverage, or both.

The growth rate may look identical in a presentation. The underlying economics could not be more different.

Company C: -10% ROIC and a target operating profit growth of 10% per year.

In this case, every additional dollar reinvested destroys economic value by definition.

Growth does not merely fail to create value. It actively accelerates value destruction.

Important Note:

To keep the intuition simple, the examples above deliberately ignored one critical layer - the cost of capital (WACC or, from the shareholder’s point of view, the cost of equity, Ke).

Now let’s put it back into the picture…

Assume a cost of equity (Ke) of 12%:

Company A: under these assumptions, it is the only one truly creating value.

It earns a 30% return on capital, while shareholders require only 12%.

The spread is wide. Compounding actually works.

Company B: it does grow, but from an economic standpoint, shareholders would be better off allocating their capital to US Treasuries - or to other lower-risk opportunities.

Growth, in this case, looks good in a slide deck, but it is inferior to simply owning a safe asset.

Company C: the worst case of all.

It raises capital at roughly 12% - its cost of capital - and then reinvests that same capital at –10% ROIC.

It loses on the return. It loses on the funding.

This is the most extreme version of the problem: a wide - and destructive - crocodile mouth between the cost of capital and economic returns.

Enjoying the content? Don’t miss out on more exclusive insights and analyses. Subscribe now and stay updated.

How to Avoid This Trap?

Before getting excited about any growth story, I now apply a very simple filter:

First, what is the company’s ROIC today?

Second, how much capital is required to sustain the current growth trajectory?

Third, is this return meaningfully above the company’s cost of capital?

If a business does not generate attractive returns on the capital it already employs, adding more capital rarely fixes the problem.

Most growth narratives fail this test surprisingly quickly.

What is The Exception to The Rule?

There is, of course, an important exception…

Some businesses deliberately operate with depressed returns in the early stages of their expansion in order to build scale, density or infrastructure that will support structurally higher margins in the future.

This is common in platform models, logistics-heavy networks and certain consumer ecosystems.

In these cases, short-term ROIC can look unattractive while long-term economics may still be compelling.

Amazon ($AMZN) looked exactly like this for a long time… and today it is a true value-creation machine.

The problem is that this narrative is extremely easy to sell.

Almost every low-return growth story claims that operating leverage, scale and future efficiency will eventually transform the business into a high-return compounder.

Very few actually do.

The distinction between genuine scale-driven economics and permanent structural inefficiency is one of the hardest - and most important - judgments an investor has to make.

Investors should be especially skeptical when the improvement in returns depends primarily on optimistic assumptions about future margins, rather than on visible changes in cost structure, asset intensity or pricing power.

Found this content valuable? Share it with your network! Help others discover these insights by sharing the newsletter. Your support makes all the difference!

The Main Lesson:

Here is the rule that quietly separates long-term compounders from expensive disappointments:

High-ROIC companies should grow.

Low-ROIC companies should fix their economics before they grow.

Growth is not the objective.

Value creation is.

When a business already earns high returns on capital, growth amplifies a good spread. It turns competitive advantage into compounding.

When a business earns poor returns on capital, growth only amplifies a bad spread. It scales inefficiency, not value.

This is why the most dangerous words in investing are:

“Returns will improve later.”

Sometimes they do.

Most of the time, they don’t.

And while growth stories may look impressive in earnings calls and investor decks, only one thing compounds your wealth over time:

Reinvesting capital at returns meaningfully above its cost.

Everything else is just a bigger business.

Not a more valuable one.

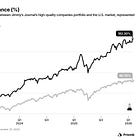

If you want to know which publicly listed companies are actually creating shareholder value, become a Jimmy’s Journal Pro subscriber. 📫

Inside Pro, I publish institutional-grade investment research focused on high-quality businesses - with a very explicit emphasis on returns on capital, economic moats and long-term value creation.

For just $229.97 per year, you get:

Access to our high-quality equity portfolio, which has delivered a 39.8% annualized return over the past three years

Real-time buy and sell alerts as portfolio decisions happen

Deep investment theses on truly high-quality businesses

Proprietary frameworks to improve your decision-making process and long-term wealth compounding

Written by a former equity analyst. For investors who think long-term.

↳ Upgrade to Jimmy’s Journal Pro now and start compounding with us.

Thanks for sticking with me until the end.

See you in the next one.

Cheers,

Jimmy

In case you missed it, here are some of our latest insights:

Disclaimer

As a reader of Jimmy’s Journal, you agree with our disclaimer. You can read the full disclaimer here.